Genetic genealogy has been all over the news and social media, with the murder case in Idaho slowly moving through the court system. Recently, the defendant, Bryan Kohberger’s attorneys have attempted to call into question the genetic genealogy that led to Kohberger being a suspect. While the judge has allowed some of the genetic genealogist’s work to be provided to the defense, he has not allowed the full information to be provided outside of the court and has cautioned the defense team that this information must remain confidential. It is unlikely that specific details will ever be made publicly available, as the judge has indicated he wants to protect the family members who were used in making the genetic connection to Kohberger.

This case has led many to question how genetic genealogy led to Bryan Kohberger as a suspect. And in more general terms, it has brought up questions about how genetic genealogy works and if it’s legitimate.

The lack of understanding about genetic genealogy has pundits across the Internet calling into question the entire field. In one example, Jonna Spilbor, a commentator on the YouTube channel Law&Crime Network on March 14, 2024, points out the defense tactic of questioning the validity of the genetic genealogy: “This genetic genealogy, which I’m sure the defense is going to argue is junk science.” After making this point, she goes on to explain what a key role genetic genealogy is playing in this case. Spilbor continues, “That is the thing, that genetic genealogy is the reason, the main reason…in terms of forensic DNA evidence, that is the thing that connects Kohberger to the crime scene, and it barely does that.” She quantifies her comment that it barely does that at all, as it is not a question of the science but of the very limited amount of blood used to create the DNA profile. Then the host, Angenette Levy, goes on to say, “They didn’t have that name connected to that DNA profile until” [the police received the genetic genealogy report]. Levy finishes with continued doubts and an open ended question about genetic genealogy. “If that wasn’t sound the way you (the genetic genealogist) figured that out…” Spilbor closes on the topic of genetic genealogy with “the main issue, this testing, and whether it’s junk science or it’s not junk science.” With so many open ended questions and doubts about genetic genealogy it would be good for any of them to bring on an expert to discuss the basics of connecting family members through DNA.

While the rest of the world is not privy to the particular work done by the genetic genealogist on the Kohberger case, meaning no one can review the work done in the sense of a peer-reviewed document, the process of how it works can be shown with a hypothetical person. The last thing I believe any genetic genealogist would want coming from this attack is to take away either the hope or the results adoptees have found through genetic genealogy, nor to cause any other court cases to find genetic genealogy results unreliable.

Someone who is hoping to learn who their biological family is is not helped by pundits calling it “junk science.”

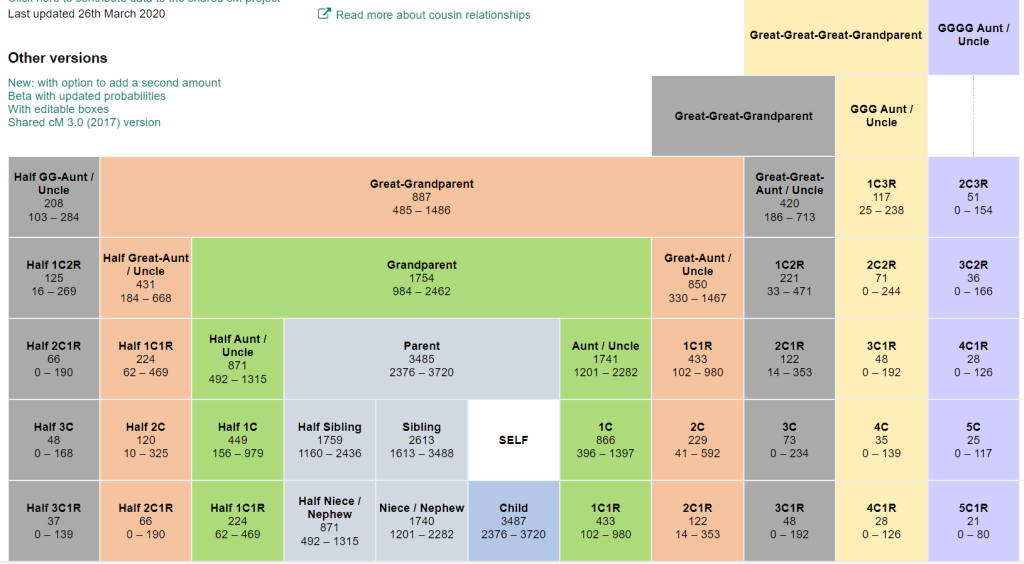

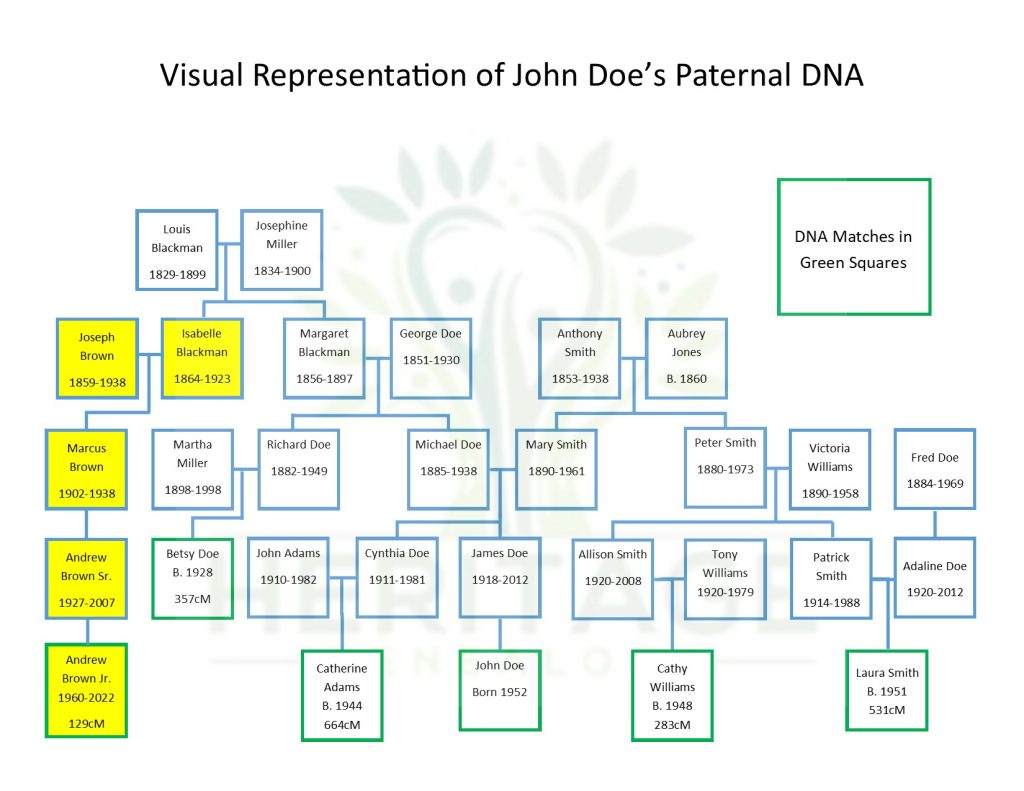

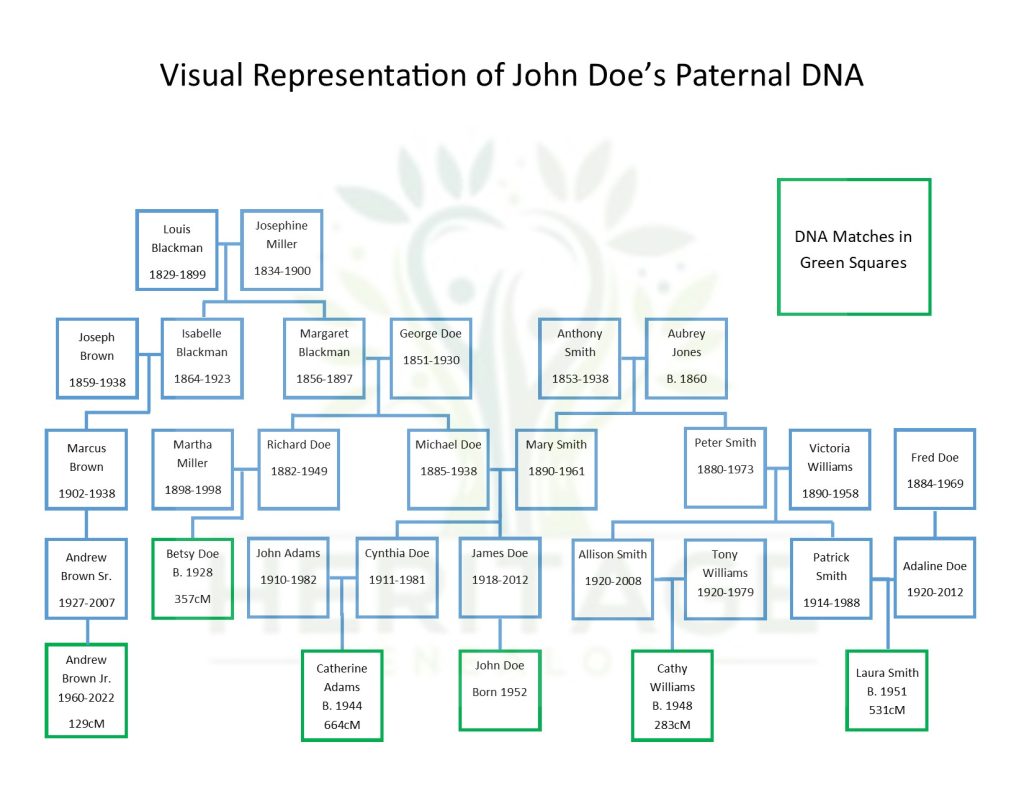

Below is a very basic example of a process that can be used. There are a number of ways to go about genetic genealogy, but what it boils down to is having an individual’s genetic profile and a list of DNA matches. Individuals are matched based on the number of centimorgans shared. A centimorgan is a unit of genetic measurement, abbreviated cM. Different experts estimate that a person has between 6,800 and 7,200 centimorgans; for that reason, 7,000cM is typically used as the average total. This means that a person receives roughly 3,500cM from each parent. Below is a visual representation, available as a tool at DNA Painter, showing the expected number of shared cM between different family members.

To demonstrate the process, I’ll go through the hypothetical genetic genealogy connecting hypothetical John Doe, born 1952, to his paternal family, whom he knew nothing about as his mother had kept it a secret. The only information John had been given by his mother was that she gave him his biological father’s last name.

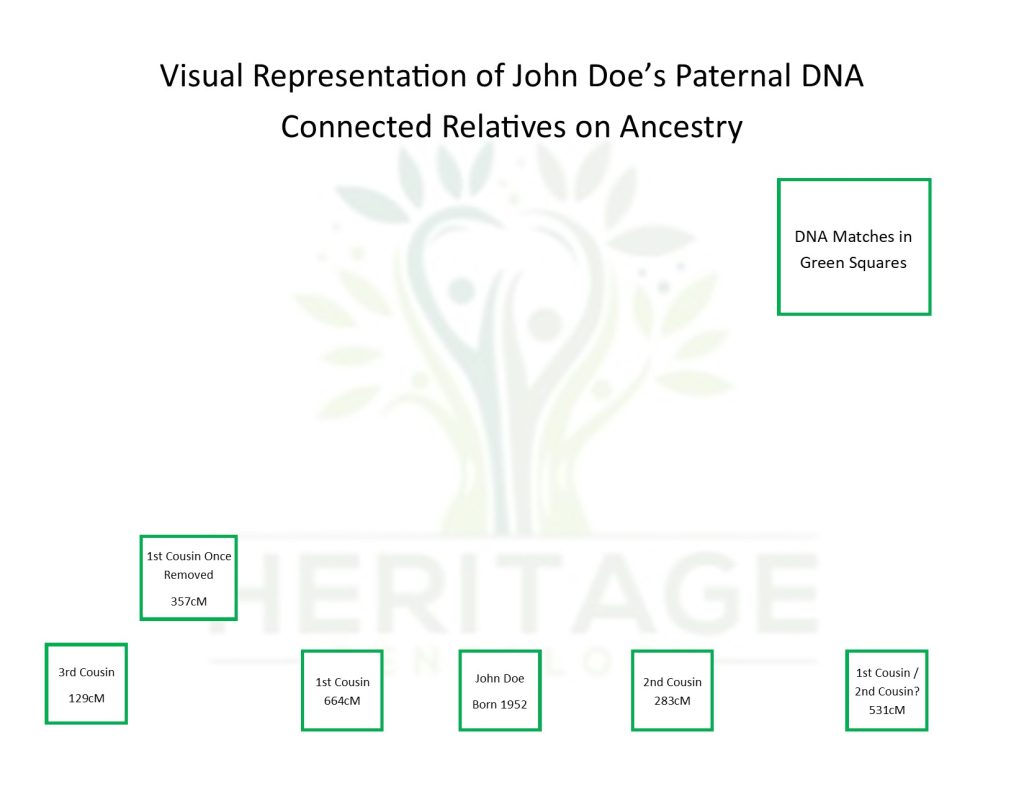

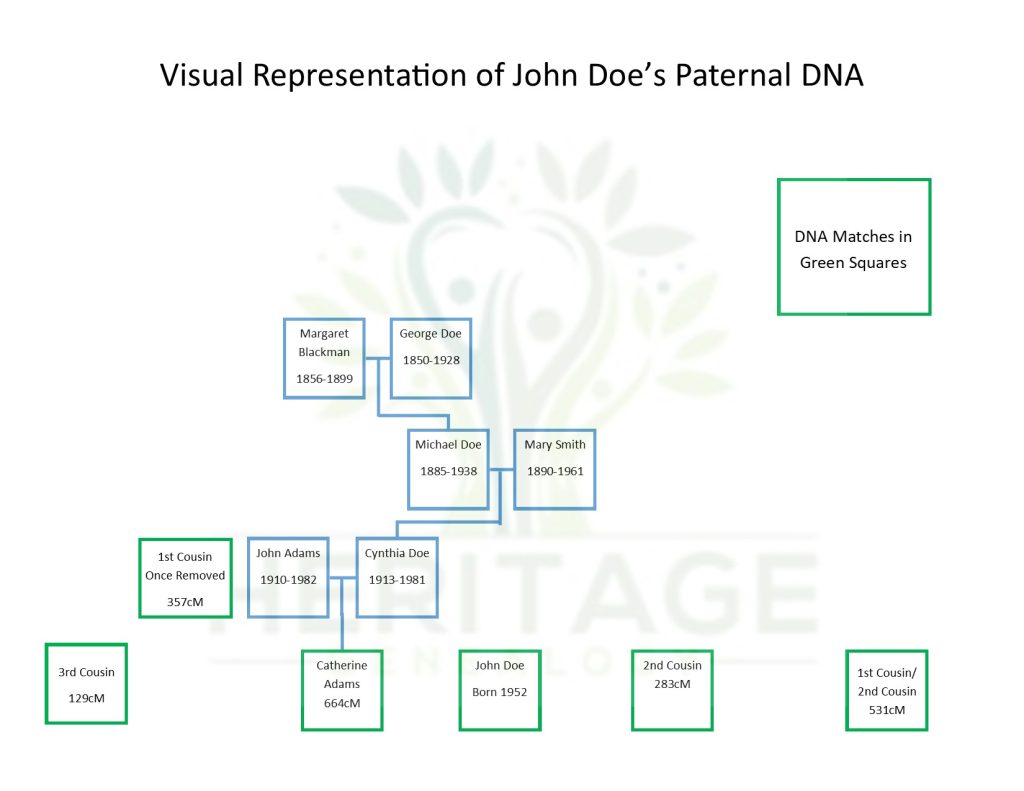

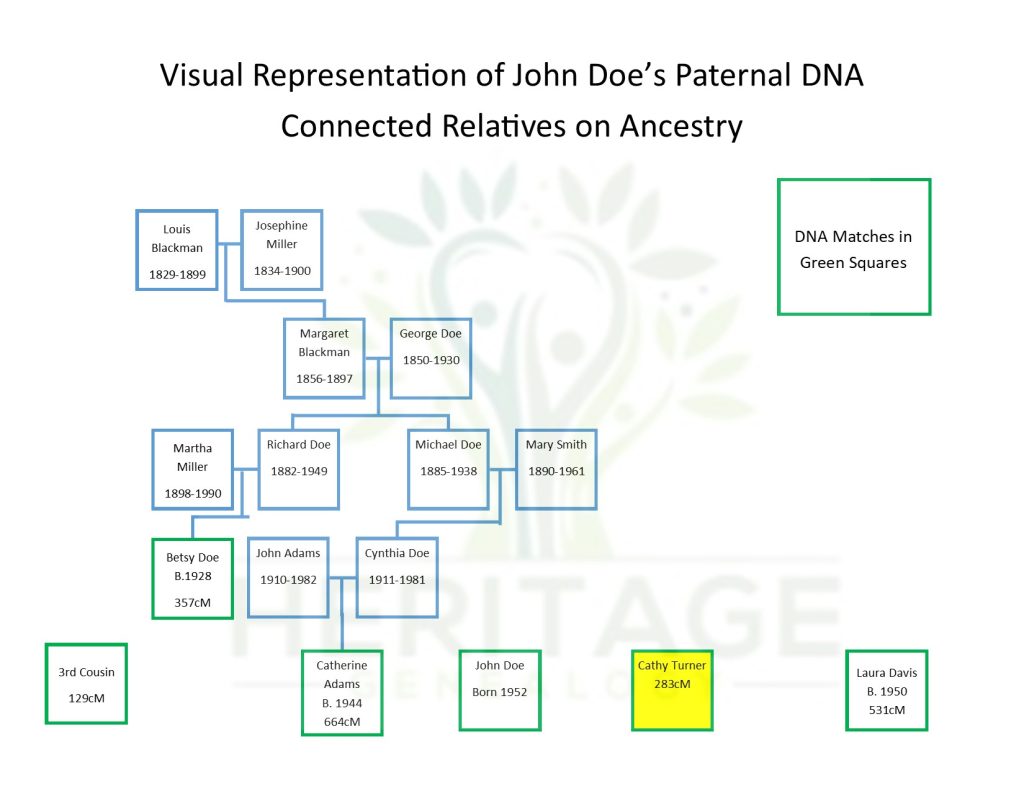

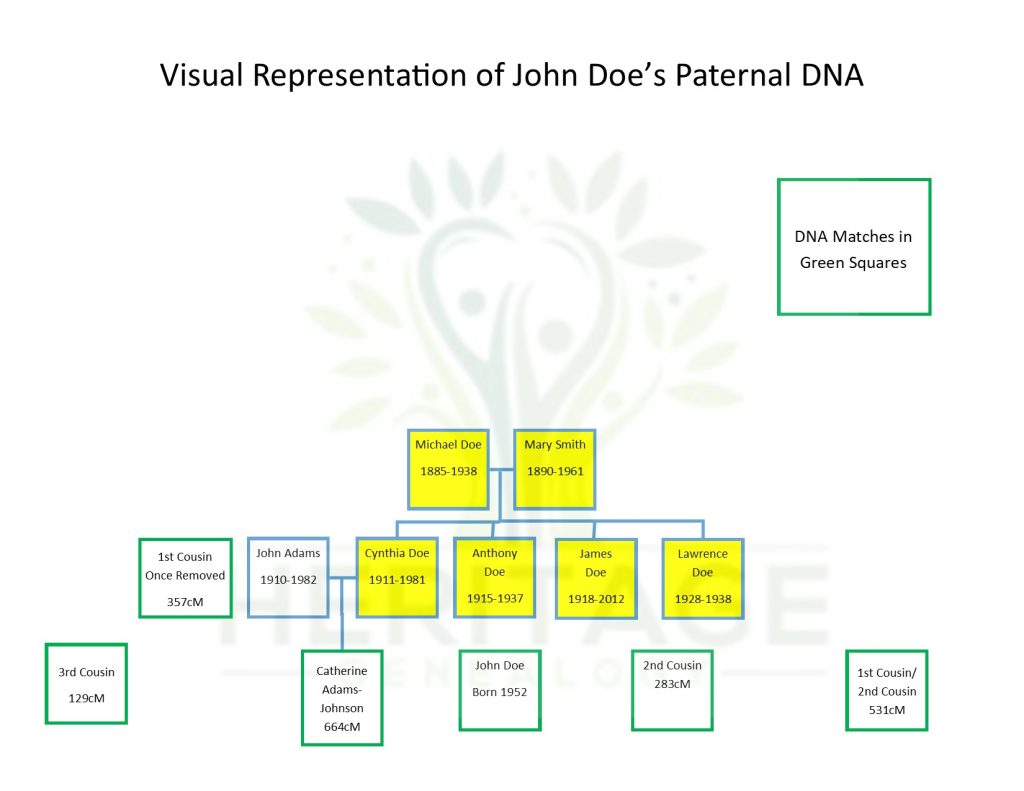

Hypothetic John had a number of good matches on his paternal side of the family. His closest match was Catherine Johnson, with whom he shared 664cM; this makes her most likely his first cousin, the daughter of one of his father’s siblings. John’s second best match was Laura Davis, with whom he shared 531cM, putting her in the first or second cousin range. His third closest match was Betsy Matthews, with whom he shared 357cM; this meant she was likely John’s first cousin once removed. John’s fourth closest match was Cathy Williams, with whom he shared 283cM, making her mostly likely his second cousin.

Below is a basic look at hypothetical John’s top paternal DNA matches and how they might fit into the tree.

These are excellent matches to work with; not always is a genetic genealogist presented with first and second cousins, but for the purpose of demonstrating how the work is done, I wanted to provide a simple situation.

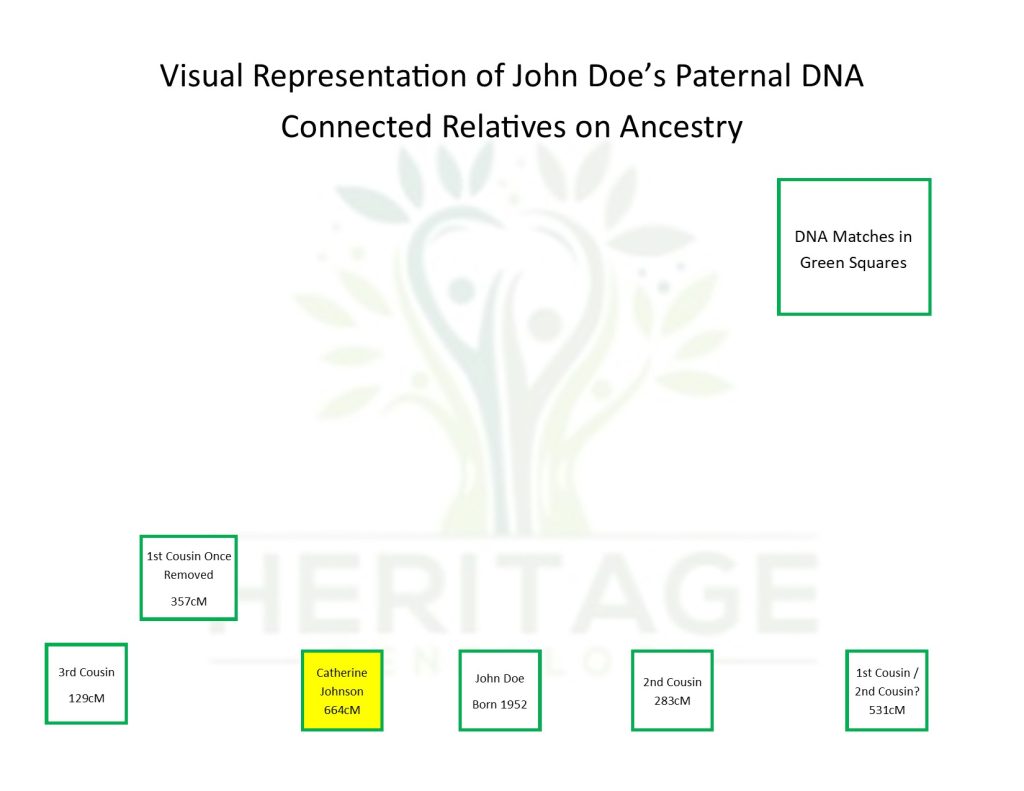

The work begins with the strongest match, Catherine Johnson, sharing 664cM. As a genetic genealogist, I start by building out Catherine’s tree. If they are indeed first cousins, John’s father will be a sibling of one of Catherine’s parents. In this case, Catherine’s online information is under her married name. Catherine’s maiden name is Adams, and her parents are John Adams and Cynthia Doe. This is exactly what I was looking to find, the shared surname of Doe. A shared surname supports the hypothesis that John’s father and Catherine’s mother are siblings.

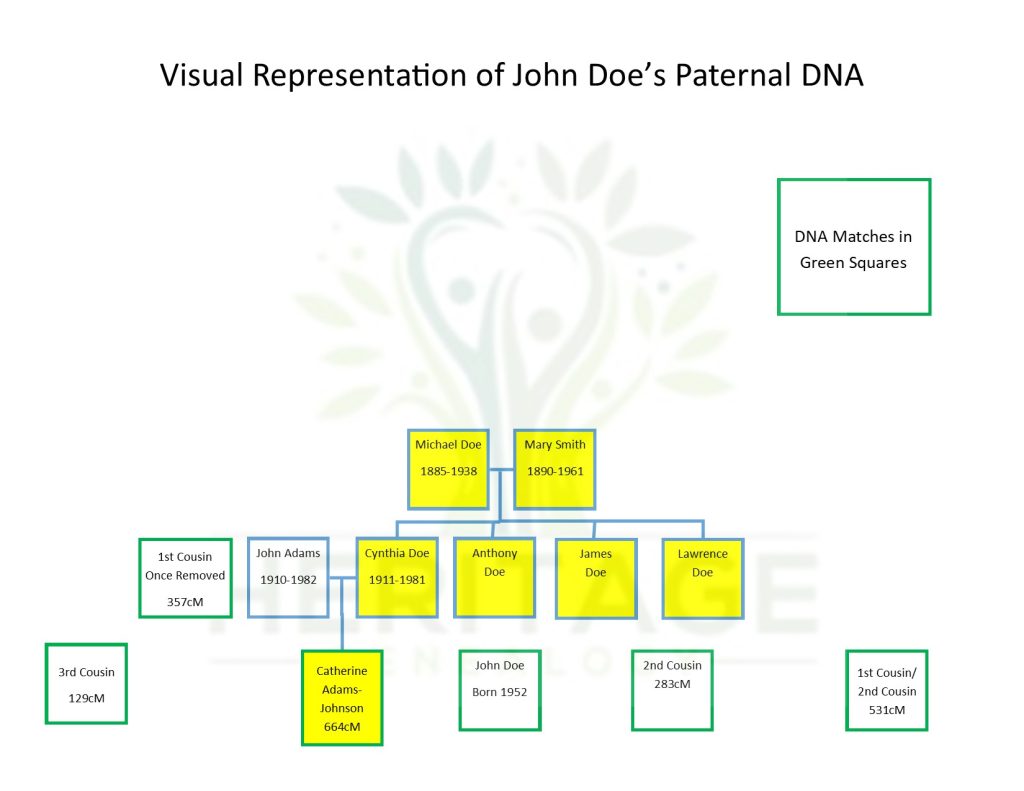

Next is further research into the family of Cynthia Doe. Cynthia was born in 1911 and appears in the 1920 and 1930 US Census records with her siblings and parents. Cynthia’s father is Michael Doe, born about 1885 and her mother is Mary Smith, born about 1890. Cynthia has three siblings listed: Anthony Doe, James Doe, and Lawrence Doe.

I focus on Catherine’s basic family tree based on her mother’s matching surname to our hypothetical John. I’ve added her grandparents on the Doe side of the family. More than likely, as the tree builds out, this information will be required to connect additional family members. As a side note, if, on an actual case, this is a very common surname such as Smith, I would have built out both sides of the family tree.

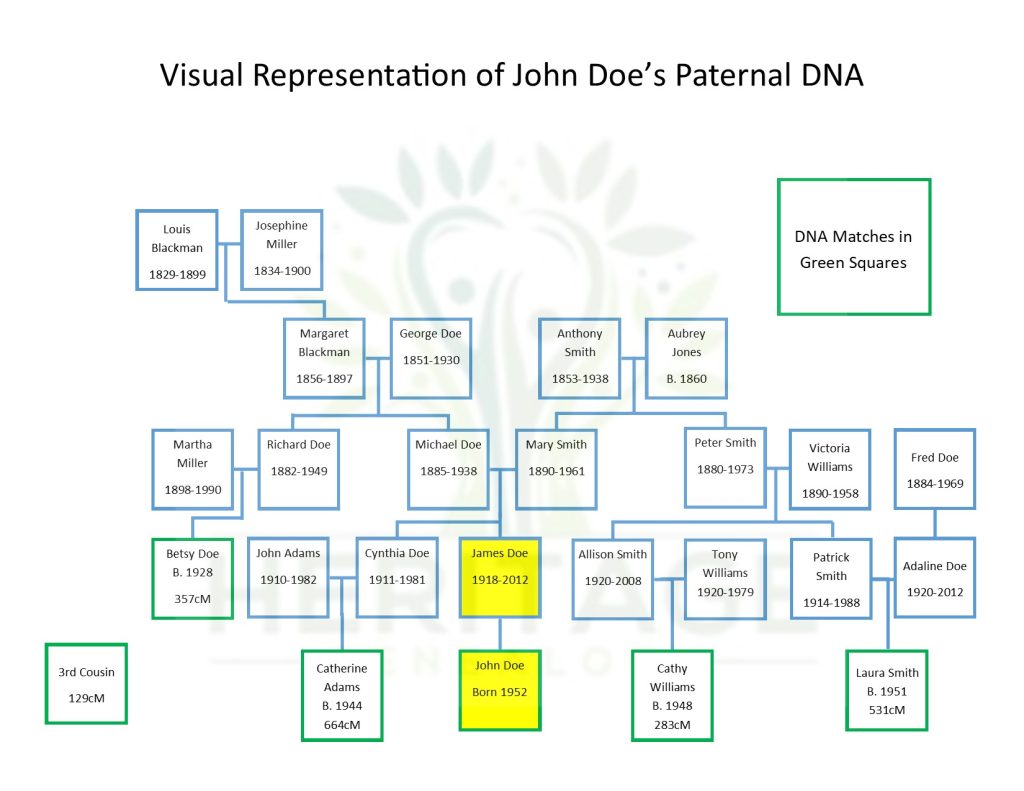

With the surname Doe matching John’s, I added one additional generation, Michael’s parents, hoping this area of the tree would continue to produce matches. Michael’s parents are George Doe, born about 1850, and Margaret Blackman, born about 1856.

Here is where processes differ. Some genetic genealogists would start by digging into each brother to find out more about the Doe family. Determining if each brother lived into adulthood can be a very easy way to eliminate potential fathers. Instead of going with a deep dive into each brother, the process I’m demonstrating is building out information on each of the closest DNA relatives first to find intersecting family members.

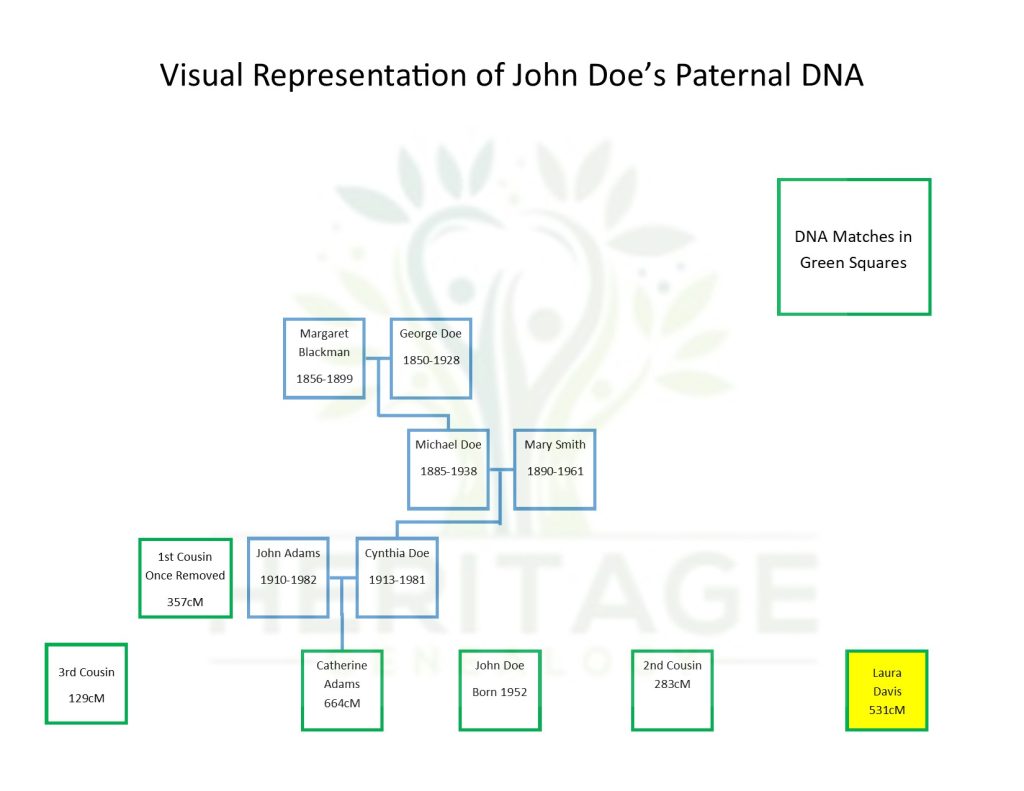

Hypothetical John’s second highest match is Laura Davis. After a brief look into Laura, Davis is clearly her married name, with no readily available information on her maiden name and no linked family tree. This one I will save for later for further investigation.

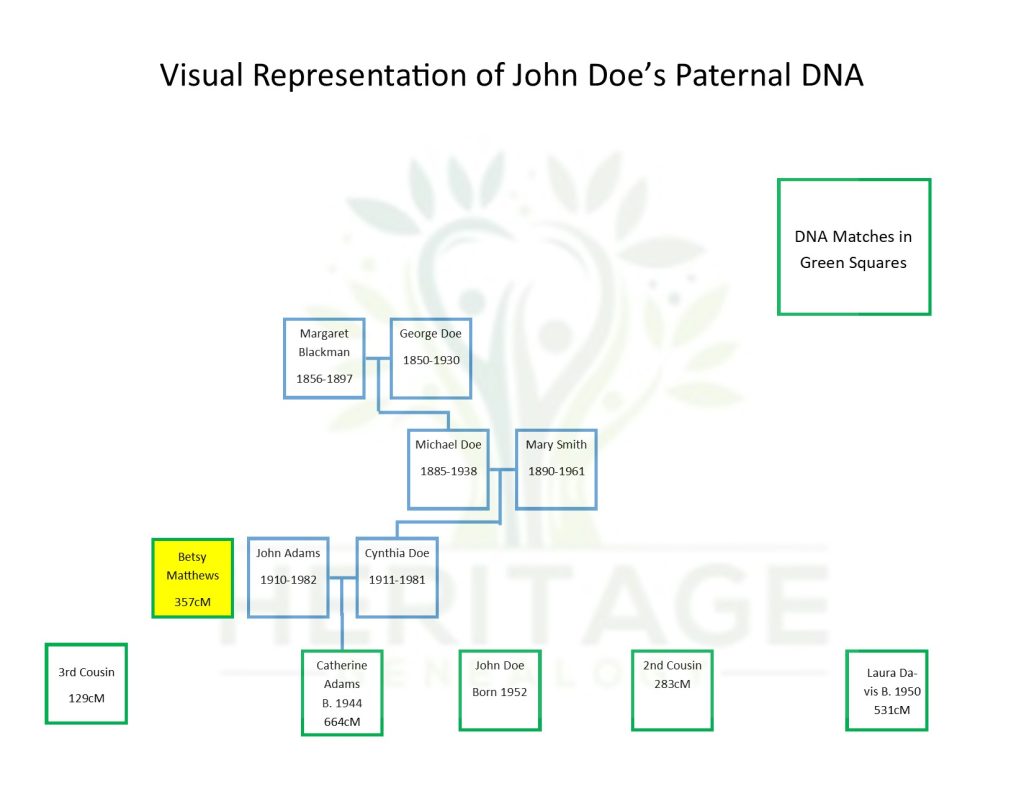

I continue on to hypothetical John’s third highest match, Betsy Matthews. Betsy’s information is also listed under her married name. Her profile is managed by someone other than Betsy, but it does include Betsy’s parents names.

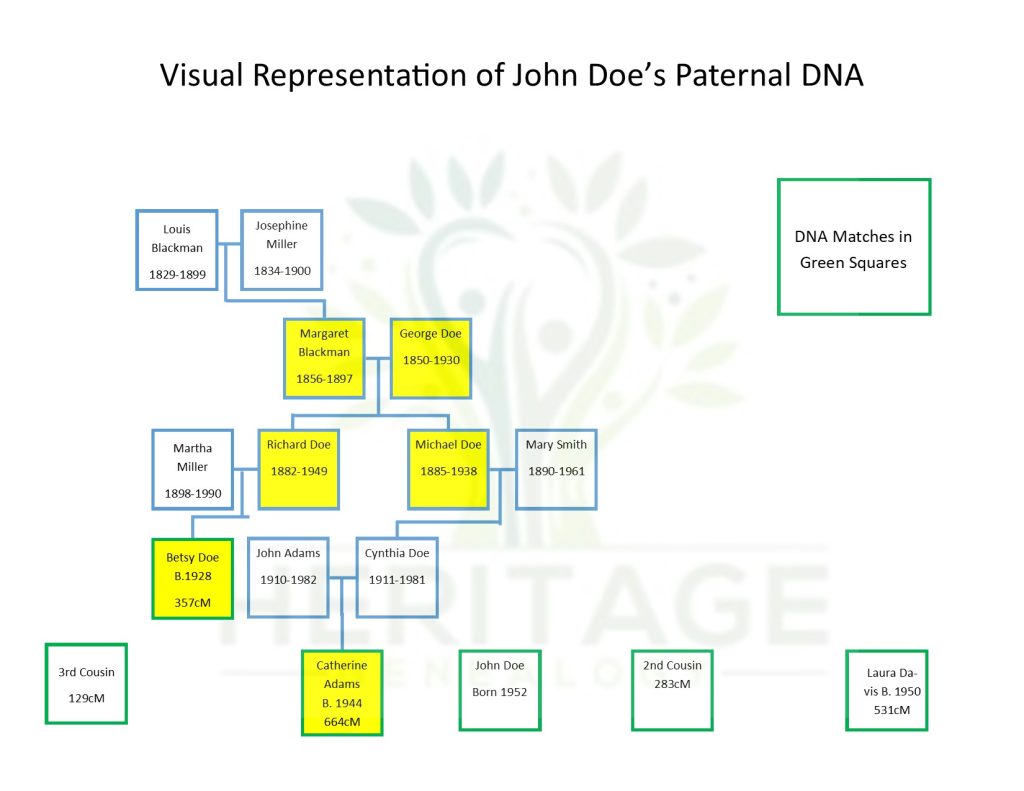

Betsy’s maiden name is Doe, and her parents are Richard Doe and Martha Miller. Looking further into Richard Doe was exactly the connection I was hoping would be there. Betsy’s father, Richard Doe, and Catherine’s grandfather from the first high match, Michael Doe, are siblings. They are both the children of George Doe and Margaret Blackman. Reviewing the shared DNA matches report confirms that John and Betsy show Catherine as a common match, as is the case when the report is run showing John and Catherine’s matches in common.

This is now a strong connection both to the surname and shared matches. I added another generation for Margaret Blackman; her parents, Louis Blackman, born about 1829, and Josephine Miller, born about 1834. At this time, I was unable to conclusively add an additional generation for George Doe.

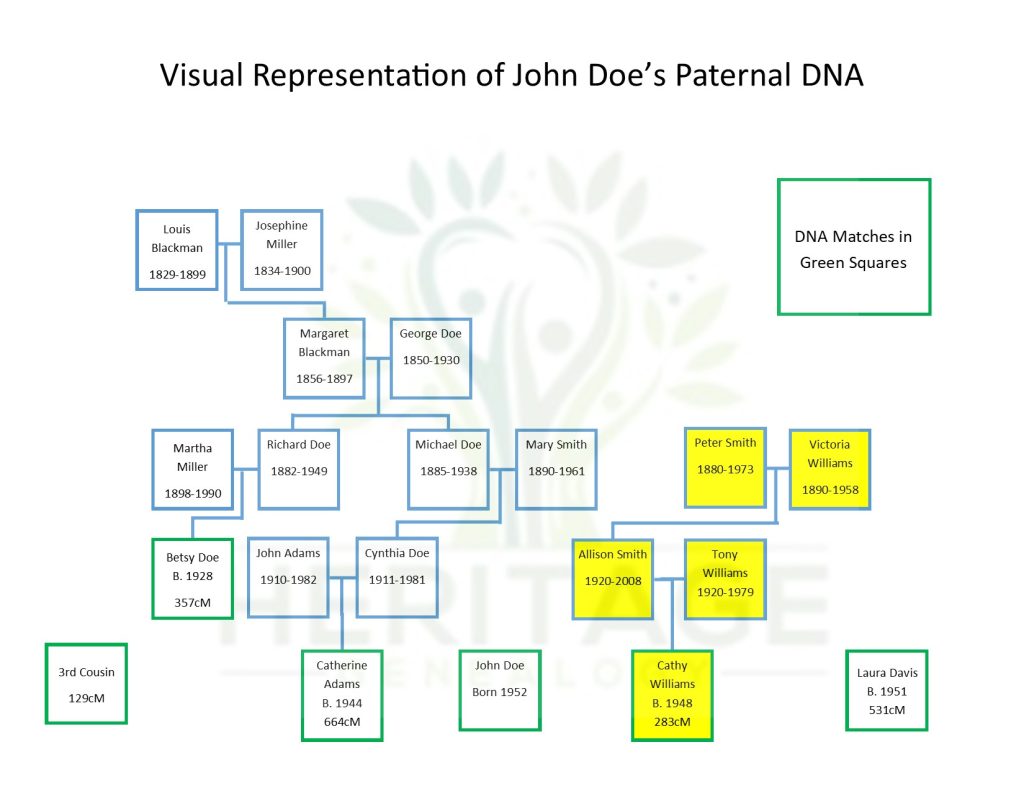

As a general guide you can now see the process as it moves down the list of connections. The next closest DNA match for hypothetical John is Cathy Turner, sharing 283cM with John.

Cathy did have a tree available, and with her parents being deceased, they were readily identified along with her maiden name, Williams. Cathy’s parents were Allison Smith, born about 1920, and Tony Williams, also born about 1920. As Smith is the maiden name of Michael Doe’s wife, I focused my search on Allison’s family. (As I mentioned before, if the real last name were something as common as Smith, I would be less likely to focus in a single direction.)

Allison Smith’s parents were Peter Smith, born about 1880, and Victoria Williams, born about 1890.

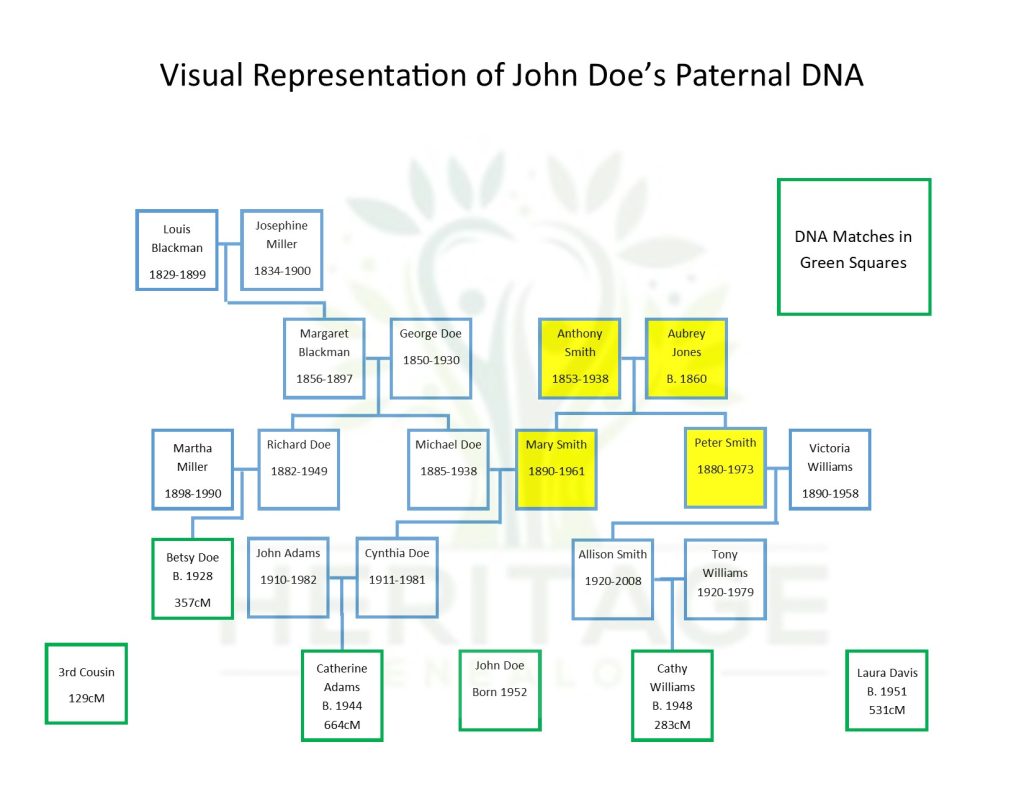

Peter was the son of Anthony Smith, born about 1853, and Aubrey Jones, born about 1860. Among the children listed on the US Census for the Smith family is a daughter named Mary, born in 1890. Further research confirms that this Mary Smith is the same Mary Smith who married Michael Doe.

Between Michael Doe and Mary Smith, I have found solid DNA matches to John Doe. At this point, it is clearly pointed out that John Doe is a grandchild of Michael Doe and Mary Smith. The only plausible alternative that should be looked into is if there is another marriage located between the children of George Doe and Margaret Blackman and Anthony Smith and Aubrey Jones. It was not unusual, for example, for two sisters to marry two brothers. This would create a scenario where you would find similar cousin DNA matches between cousins. For the sake of simplification, that did not happen in the family of hypothetical John.

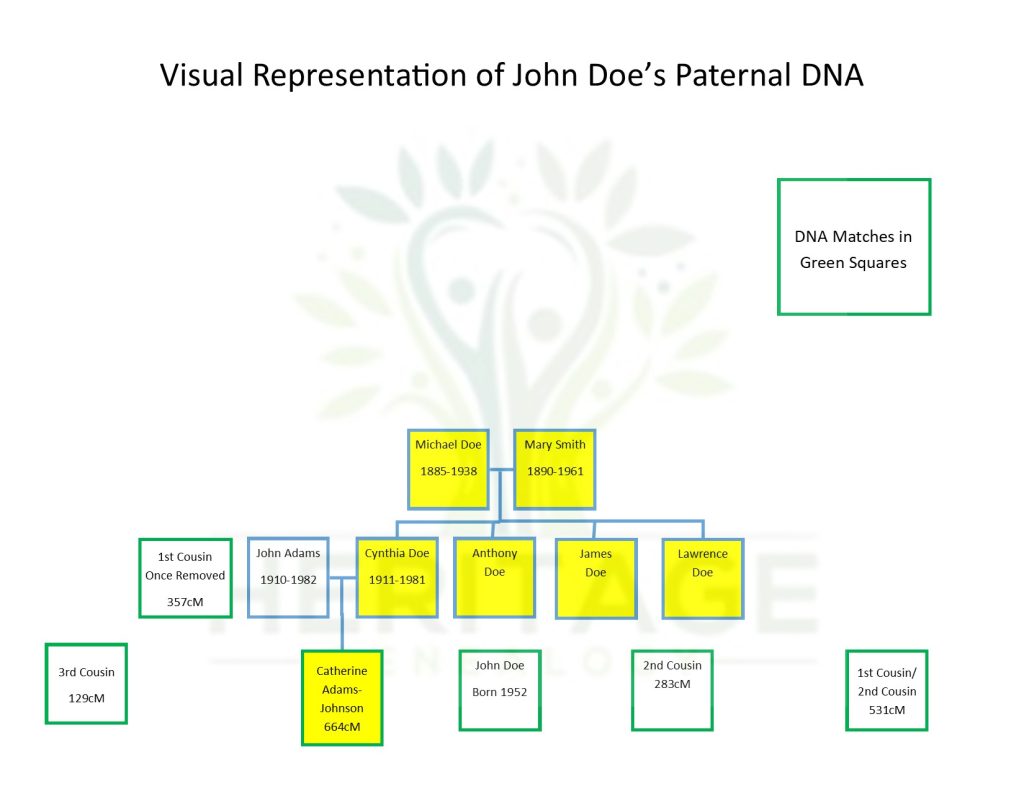

I will now go back and look into the children of Michael Doe and Mary Smith, the siblings of Cynthia Doe, Anthony Doe, James Doe, and Lawrence Doe. Lawrence Doe, born about 1928, was the quickest to be eliminated. He was recorded as dying young in 1938 and was buried in the same plot as his father and mother. Having only reached the tender age of ten, he was clearly not the father of John. Anthony was born about 1915 and died at the age of 22 in 1937. As John was not born until 1952, this eliminated Anthony as the father as well.

This leaves the only other known son of Michael Doe and Mary Smith, James Doe, as the father of John Doe. James Doe did have several other children; should someone like hypothetical John choose to reach out to his half siblings, that would be the most concrete way, outside of testing James’ DNA, if he were still alive, to prove John is the son of James.

An argument can be made that I should have investigated them first. However, even if I had done that and determined that Anthony and Lawrence did not have any children, to fully confirm the relationship, I would have still needed to go through and verify the relationship with John’s other high matches to demonstrate the strength of those relationships.

If this was the case of the unknown male DNA, like in the Bryan Kohberger case, there is evidence of an absolute DNA match to a grandchild of Mary Smith and Michael Doe. The match can’t be to a child of Cynthia Doe, as that DNA match would be much higher and show as a sibling match to Catherine, not a first cousin match. The two other siblings of James and Cynthia have been eliminated as dying before having children. So the conclusion is sound, and should the same raw data be provided to another genetic genealogist, the same conclusion is the only one that fits together the DNA matches without any outliers.

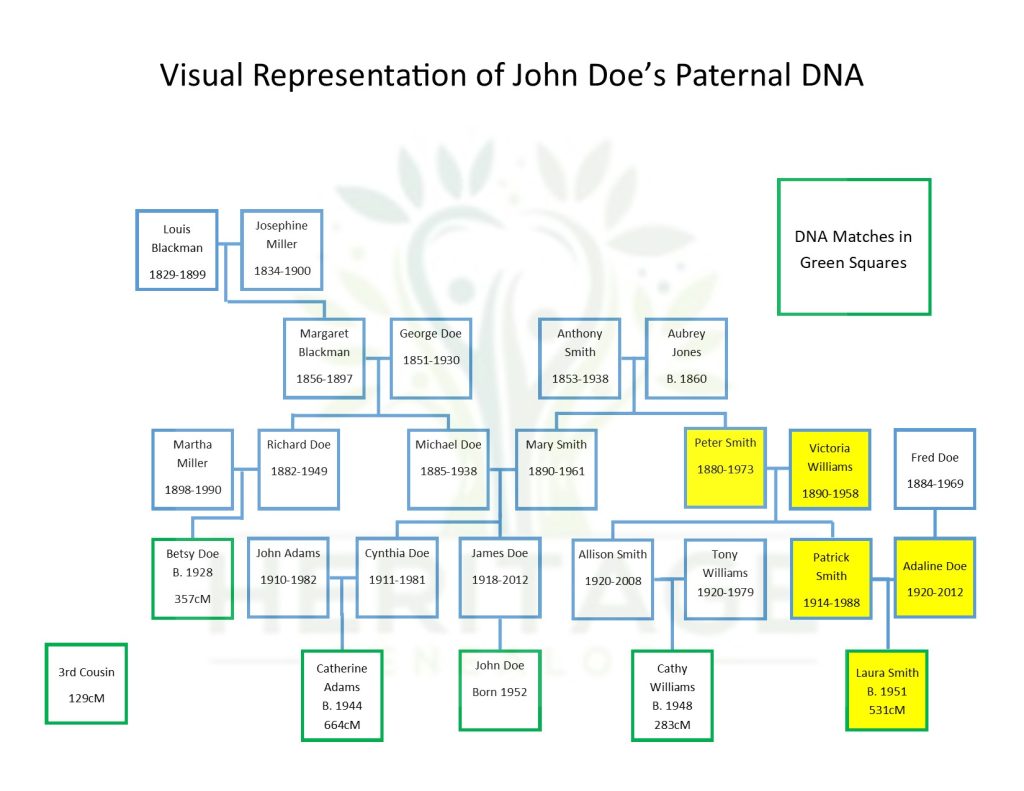

To really clean the tree up since there is one outlier right now, Laura Davis. With further expansion of the Smith side of the tree, as Laura shows Cathy as a high common match with John, I found that Laura’s maiden name is also Smith. Laura is the daughter of Patrick Smith, Allison Smith’s brother, and his wife, Adaline Doe. Patrick was born about 1914 and is the son of Peter Smith and Victoria Williams. This makes Laura another second cousin of John’s, however, with a higher than expected number of centimorgans in common. This may be a result of Laura’s mother, Adaline Doe, sharing the surname with John’s grandfather. There is a good chance that further research into Adaline’s family will locate a Doe relative in common, increasing the amount of shared DNA between John and Laura.

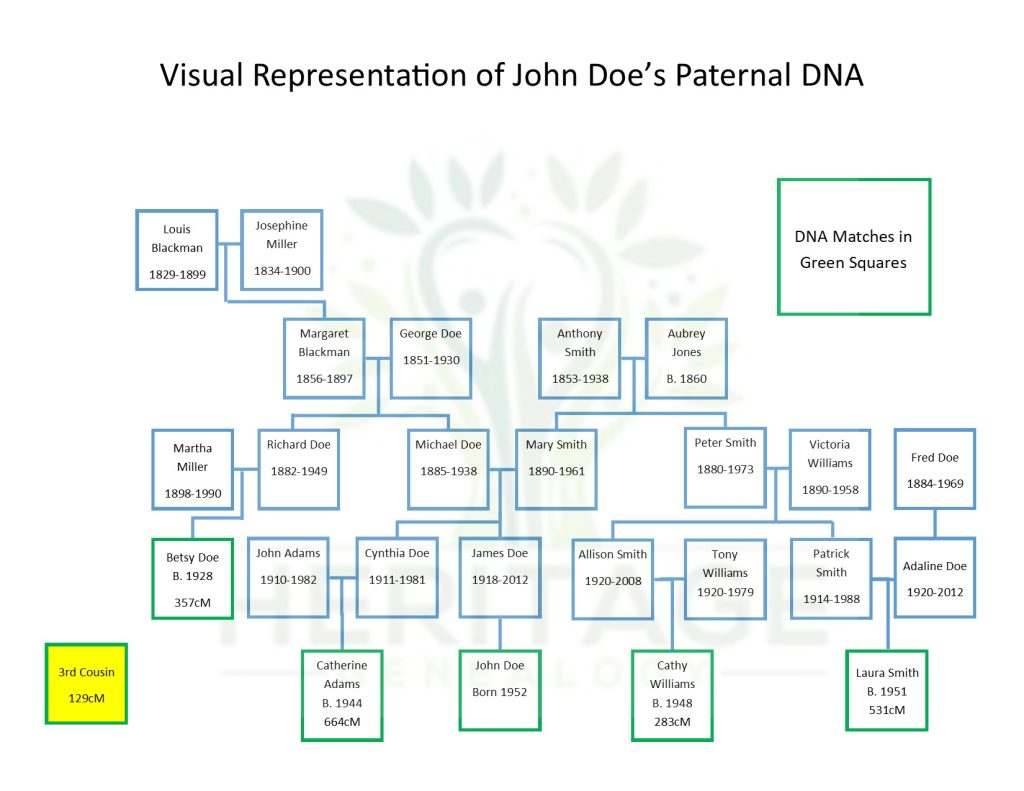

Lastly, to round out the matches a little further, there is a third cousin match to Andrew Brown Jr., who shares 129cM with hypothetical John.

Andrew recently passed away but is in a tree managed by a family member, which provides clarity on the relationship to John. Andrew’s father is Andrew Sr. and Andrew Sr.’s father was Marcus Brown, who was the son of Joseph Brown, born about 1959, and Isabelle Blackman, born about 1864. Isabelle is another daughter of a family I already documented in the tree, Louis Blackman and Josephine Miller.

Here is the detailed paternal tree laid out for hypothetical John; he now has an idea of how he fits into his paternal family.

If you have further questions about genetic genealogy or are looking to hire someone to help you Find Your Family or work on any other genetic genealogy project, don’t hesitate to Contact Us.